The Evolution of PhilPhlix

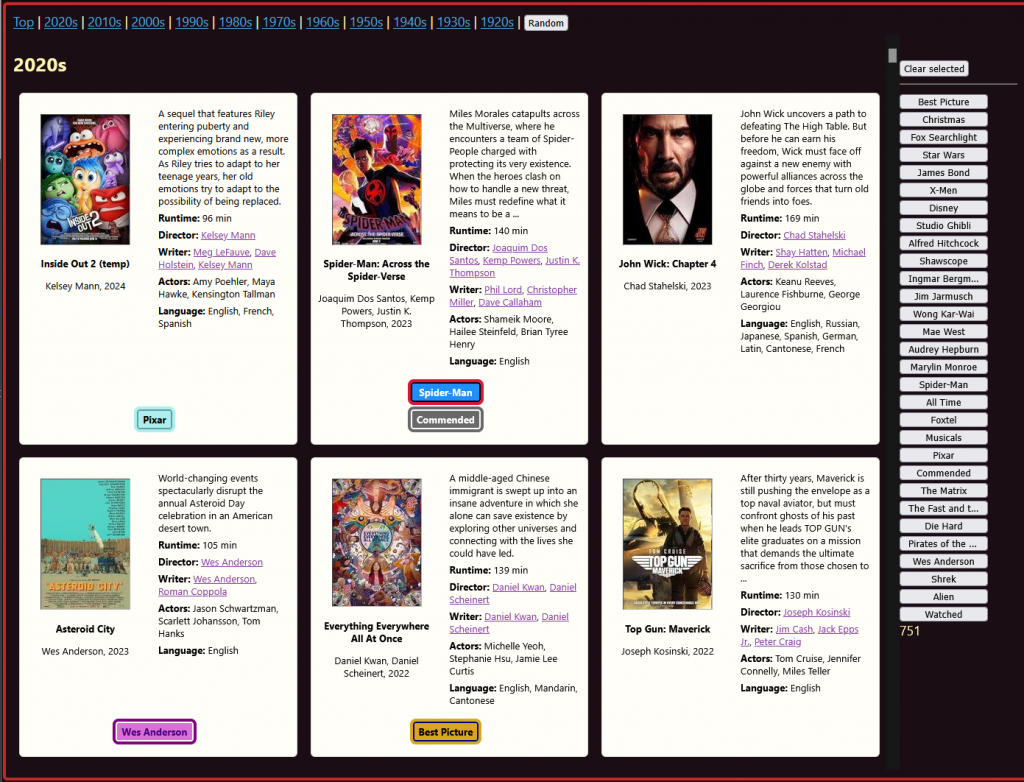

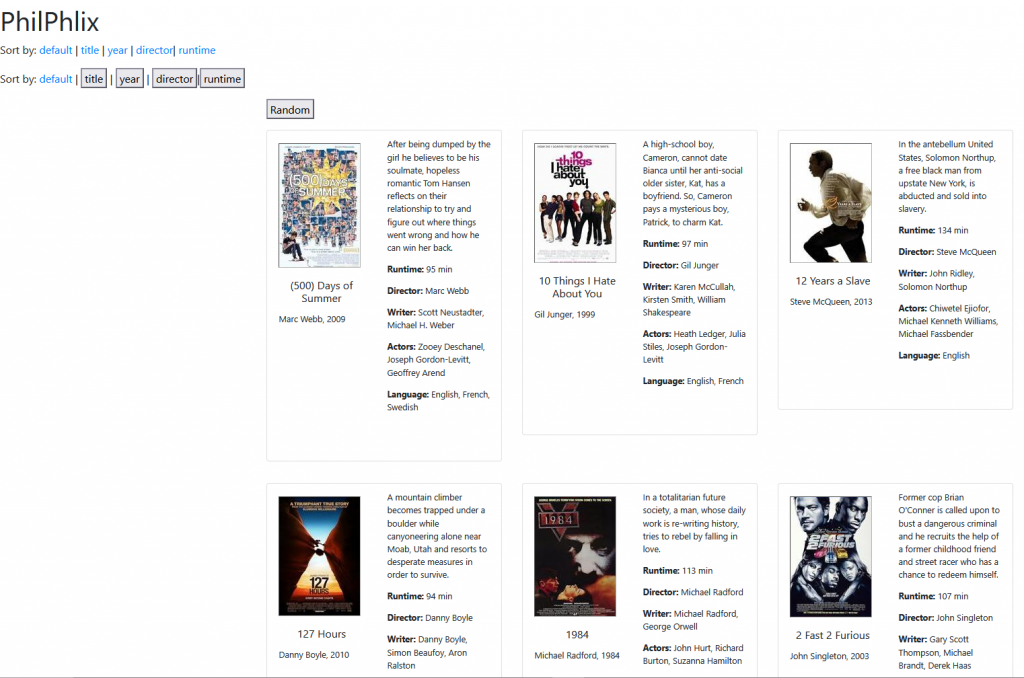

A couple of days ago I uploaded a static version of my WIP movie catalogue at https://philbetts.com/philphlix/philphlix.html – go and have a little looksie.

I’ve been tinkering away for years building tools, and have always intended to write about the process. This is continuing my habit of writing one (1) blog post every approximately twelve (12) months. See the previous entry from December 2024!

This is more or less a direct continuation of that intent. Will it be another 12 months before the next? Maybe! I’m writing it as an exercise in reflective practice. I’m aiming to write about technical concepts for a non-technical audience, but over time, hope to get into some pretty heavy design, philosophical, and architectural topics. There’s a lot of scene-setting to do, and in doing so, I’m hoping to share and give insight into design and architectural decisions, back-end and front-end, and the process and challenges of creating apps from scratch. This is an actually agile project in the original sense of it, in that it’s blue-skies, no-set-destination, try-something-out, iterate-and-pivot-based-on-user-(my)-input. Not, you know, a mostly useless management fad with infantalising shibbolethean language and rituals, and self-governing ‘pay-to-play’ qualifications that end up just being an excuse not to project plan.

A note on accessibility:

If this continues, I’ll need workflows to be able to display code and snippets of work, as well as video recordings etc. I have a vague intention at some point of either tearing down this old WordPress site and replacing it with something static, or going full hog and spinning up a server with my platform and a blog app sitting on top, as the ultimate proof-of-concept. Until such times I’ll be making use of screenshots, acknowledging that screenshots of code and interfaces aren’t great for e-readers. Apologies, it’s definitely something on the back of my mind that I know I’ll need to address!

The Virtual Blu-Ray Money Bin

The short of it is I have a collection of 750+ Blu-Rays (actually closer to 800, I need to do some updating), and it’s too many to keep track of. I’m a streaming service conspiracist (in that I don’t believe in streaming services – or at least, I don’t think they’re good for us long term), and a collector who absolutely loves stuff. I wanted a way of figuratively diving into my pools of riches and swimming around, Scrooge McDuck style – throwing handfuls of movies up into and flopping back onto the pile, shiny discs raining down with a pleasant tinkling, like wind-chimes. I wanted a way to make my collection more present and discoverable (instead of out of sight, out of mind), and I wanted something that will encourage me to watch more movies and work my way through the massive backlog – I collect much more than I watch, and am only about half way through watching these.

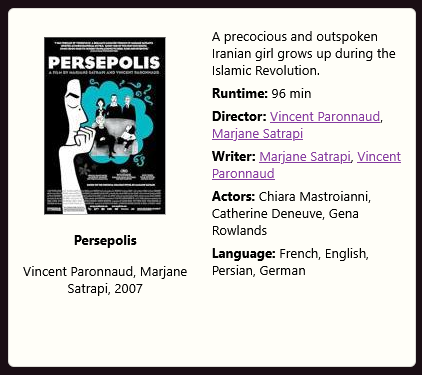

To that end, I’ve been iterating over a catalogue/library app – we’re working with movies, but the fundamental principles and most of the design choices are transferable to just about any collection management – from something like Calibre, the eBook management platform (and one of my favourite pieces of software ever designed), to Plex, the server and interface I use for managing my music collection, to Endnote, a citation management tool, to shopfronts doing e-commerce. They’re all just variations on a theme – data, metadata, images and other assets, sort, tags, collections, playlists, navigation etc. etc. Though I’m building an app to manage my movie collection, in the back of my head I’m always thinking about a generic library app that can be used for anything. And I have a lot of opinions on such things.

So, how did we get to the latest iteration of PhilPhlix? There’s maybe 50-60 different programming concepts tied together at this point. There’s a bit more functionality on my local server where I host and develop it which I’ve stripped out of the static site (mostly the CRUD – create, retrieve, update, delete functions – i.e. database interactions), but I’ve exported out a static version to be able to demonstrate it here without the need to host the dynamic content on a public server (with its associated costs and risks) for the foreseeable future. What follows is a partial overview of the journey so far.

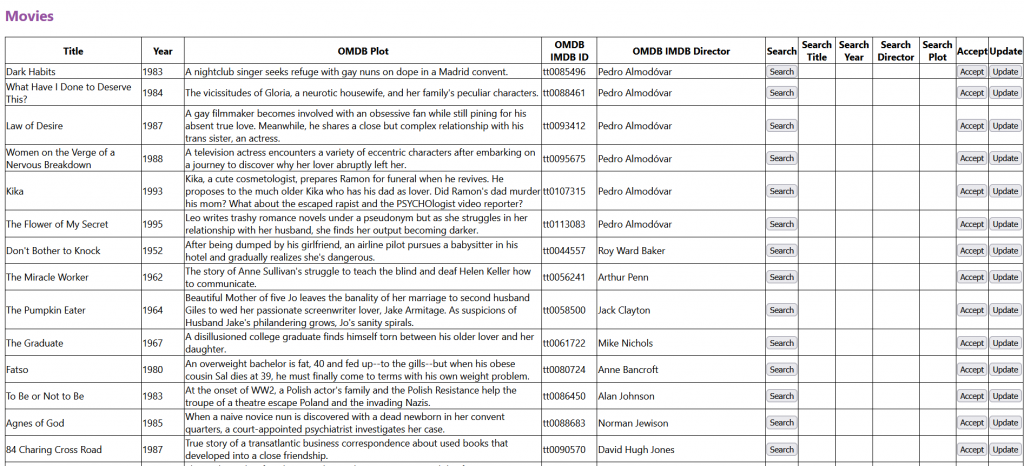

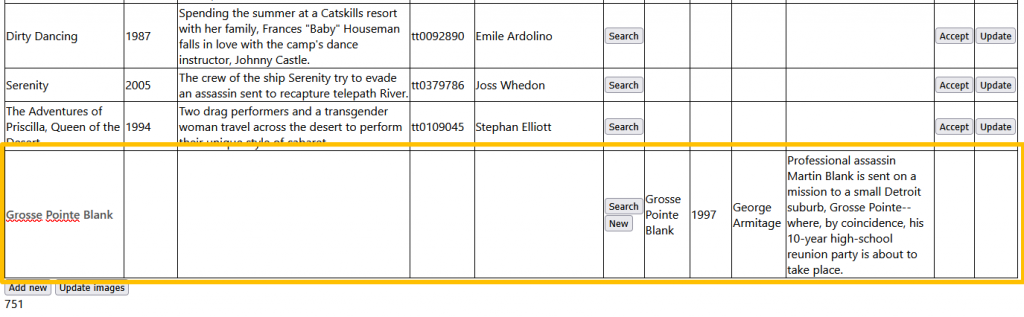

The Data

The list of movies began life, as these things are wont to do, as a list in a spreadsheet. In parallel to building the site platform (which I wrote about a year ago), one of the first things I did was tap into the API at https://www.omdbapi.com/, an open database equivalent of IMDB. I built an incredibly crude page that enables me to enter in and search for a movie title, then retrieve the details, save, and modify them. It’s still the mechanism I use to add any new film I acquire, though it’s in fairly strong need of an update, and there are some limitations I’ll address later (in short: description fields are cut off beyond a certain number of characters; multi-entry fields (like actors, directors etc.) are stored in a single comma separated entry, which doesn’t lend itself to being split out and made interactive; you only get one default poster to chose from; it only has about 96% coverage etc.):

You search by title (and year/IMDB ID if you need it), and it fetches the details, and if it’s the one you’re looking for, you save. Huzzah!

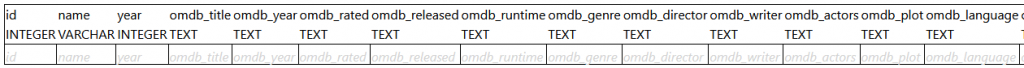

Once I could retrieve movie data, I built a corresponding table in an SQLite database to store it, which looks a little something like this:

Basically, it stores the API’s returned fields, plus a few standard ones which are copied from the OMDB ones – these are separate display fields. I wanted to be able to overwrite the OMDB ones in a non-destructive manner (in case I need to refer back to them later). At some point, I’ll split these out and clean them up, but it does what I need it to for now. It also retrieves and saves the thumbnail poster, so there’s a little extra work going on behind the scenes.

Overall, while it’s crude, clunky, and has a bunch of UX gaps, it’s functional. Each entry is looked up and saved manually – when I started I was probably at 400ish movies, and through each round of updates I usually add 15-20 more titles, as I generally make bulk purchases during sales, or buy boxed sets (I’ll typically wait for the average price of a movie to come down < $10 AUD – and can sometimes get them for quite a bit less).

At this point I had a table of movies and movie details – I needed a way to display them.

The Interface

To build the pages dynamically, behind the scenes in the back-end I’m using Python, a Flask dev web server, the SQLite database, and Jinja templates, to model the data and populate a page. I’m on round 2 or 3 of this app’s iterations, and the front end is now fully vanilla HTML, CSS and JS. The first version however used the Bootstrap CSS framework, as I wasn’t really across responsive CSS at the time, and that seemed like a faster way to get going:

It’s not wildly dissimilar to what it looks like now, but I have a MUCH deeper level of control since re-writing the CSS from scratch. You can see from this earlier screenshot, for instance, in fullscreen view it only displayed three columns with a lot of whitespace, which I think was a default Bootstrap configuration.

You can also see more or less from the beginning there were options to sort by different fields (in ascending or descending order) – something that I’ve temporarily stripped out of the static version on the site (as it needs a Flask server to process), but remains in my local version. This was done at both a template level using query parameters (“?order=title”, “?order=year” etc.) that change the database query and data modelling server-side, before passing it off to generate the template; and a local, browser-side sort option, implemented with Javascript. This front-end/back end replication of features is something I encounter lot, and it’s an interesting dynamic I’m keen to explore more. I find I’m often reflecting on the need for both server-side and browser-side implementations of functionality, their ease and limitations, and considering issues like code bloat and how to keep them in synch (naming conventions, how to keep track of modifications with downstream consequences etc.) For example, if I’m creating a template element for generating an HTML response (like a movie display card), and then on that page I can add/create an additional movie entry, should I fetch the template via AJAX, or should I simply create new elements in JS? Definitely worthy of its own exploration some time.

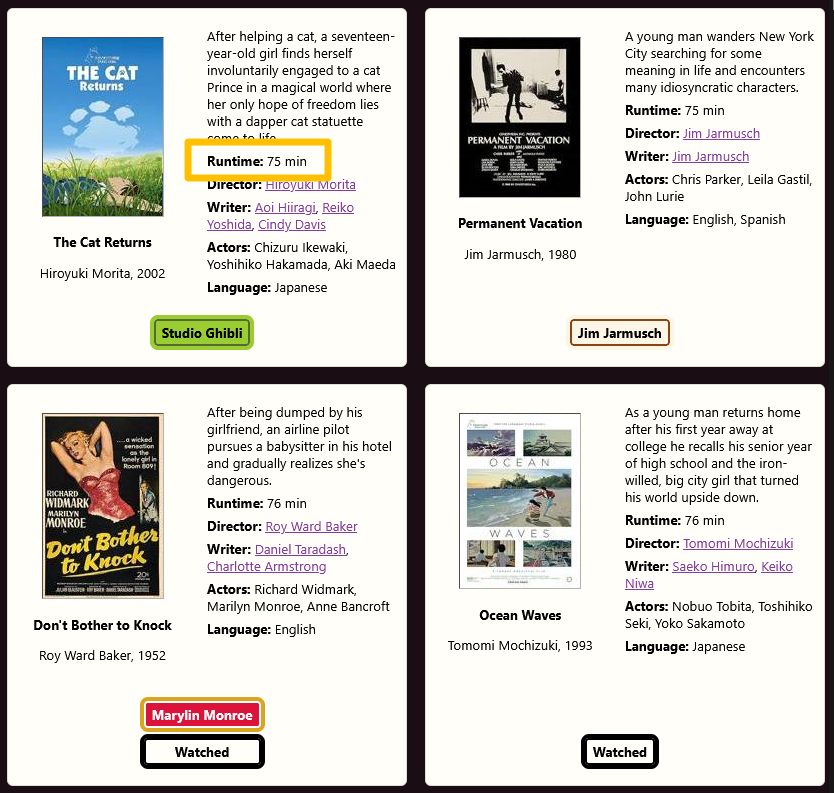

One of my favourite features I’d like to draw attention to from the early build is the “sort by runtime” (?order=runtime) option (which you don’t have access to, but there’s a static version of ‘sort by runtime’ here):

(You can also preview a category I’ve hidden in the static version – “Watched” – more on this later.)

I’ve used this feature a few times already when I’ve wanted to watch something I haven’t seen, but I’m just not prepared to commit to 2+ hours. It’s interesting to me that there’s nothing technically different about this feature from any other sort option, but non-standard sort fields are rarely seen in user interfaces. There are stifling limitations in most web shopfronts and product galleries. With most built on very generic shopping platforms, you’re usually left with a small number of common sort fields, typically limited to:

- Name

- Date (added date)

- Price

It surprises me that if I’m looking for, say, a new wallet, I generally can’t sort by something like colour, or material, or product dimensions. These properties are sometimes available via filtering (if you’re lucky), but filtering and sort (and search) are usually implemented as two (three) separate paradigms. I generally can’t go “show me all your available wallets, sorted from smallest to biggest”. At best, I might have a filter that can “show me wallets between x and y size” (like “show me flights that depart between x and y o’clock”), or “show me size M wallets”, but then they’ll probably be sorted by price, or date added etc. The comparative feature I want is not available to help me make my choice.

Online shopfronts typically aren’t built to aid discovery, and have very little consideration of user sensemaking (i.e. how the user explores, models, and makes sense of their options). This theme will come up repeatedly in my approach. Amazon is a prime (wahey) example of this – probably the worst shopfront interface on the internet for managing results. It’s truly baffling, and probably results from some dark pattern to drive sales of their own tat.

Collections v1

At this stage, I got to the point where I had my data set, I could display it, and I had a basic way of sorting the display. It was time for more features, which introduces more complexity.

I mentioned I’m a collector and a completionist. If I buy one, and I like it, there’s good chance I’ll buy all. I like looking at my collections. I also mentioned that hundreds of movies are too many movies to meaningfully scroll through. From the outset I knew I’d want some sort of collections functionality. These are key to any good library management.

The first thing I started with was identifying the Oscar – Best Picture winners (I had about a third of them when I started this – now I have about 10 movies to go.)

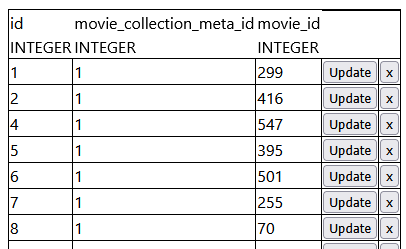

A new feature meant making modifications to the database structure with new tables, introducing new SQL queries, and subsequent modelling. The join table connecting movies to categories started as this:

Up until this point, every movie had its data contained in a single row of a single table. It was essentially a spreadsheet, with the same categories of data. Now, I had a situation where a property only applies to a subset of them. ‘Best Picture’ was one category I wanted – there are theoretically countless others. This is the way I typically work – start with an applied use-case – here, a single category – and then think about the abstracted model underneath it. Proof of concept, then generalisation.

I didn’t have an interface for adding categories at the beginning, but I didn’t care. The proof of concept was around joining up tables and some notion of filtering the full collection to a smaller subset. I added the “Best Picture” data to the join table manually, i.e. directly editing the database (the screenshot above is a browser-based DB editor I made, for viewing, adding, updating, and retrieving SQLite rows.)

Now I had the data, I needed to update the data model and the view, which meant the SQL query. I was still pretty early on in learning the Flask request syntax, so the easiest thing at the time was just to just create a new endpoint route “/oscars”, copy and paste across from the main movie modelling, and update the database search query to filter for movies with the “Best Picture” category. Successful proof of concept, but very manual – it wasn’t integrated, and to update it I needed to directly modify the database (including looking up unique IDs), and a standalone page.

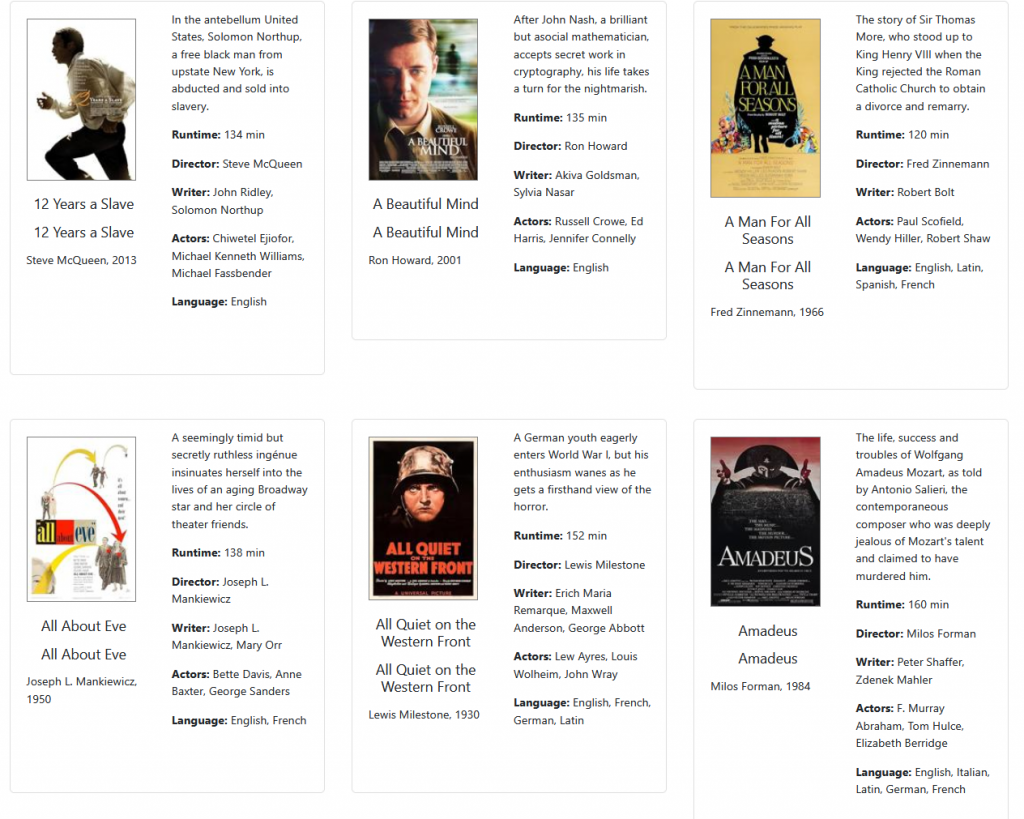

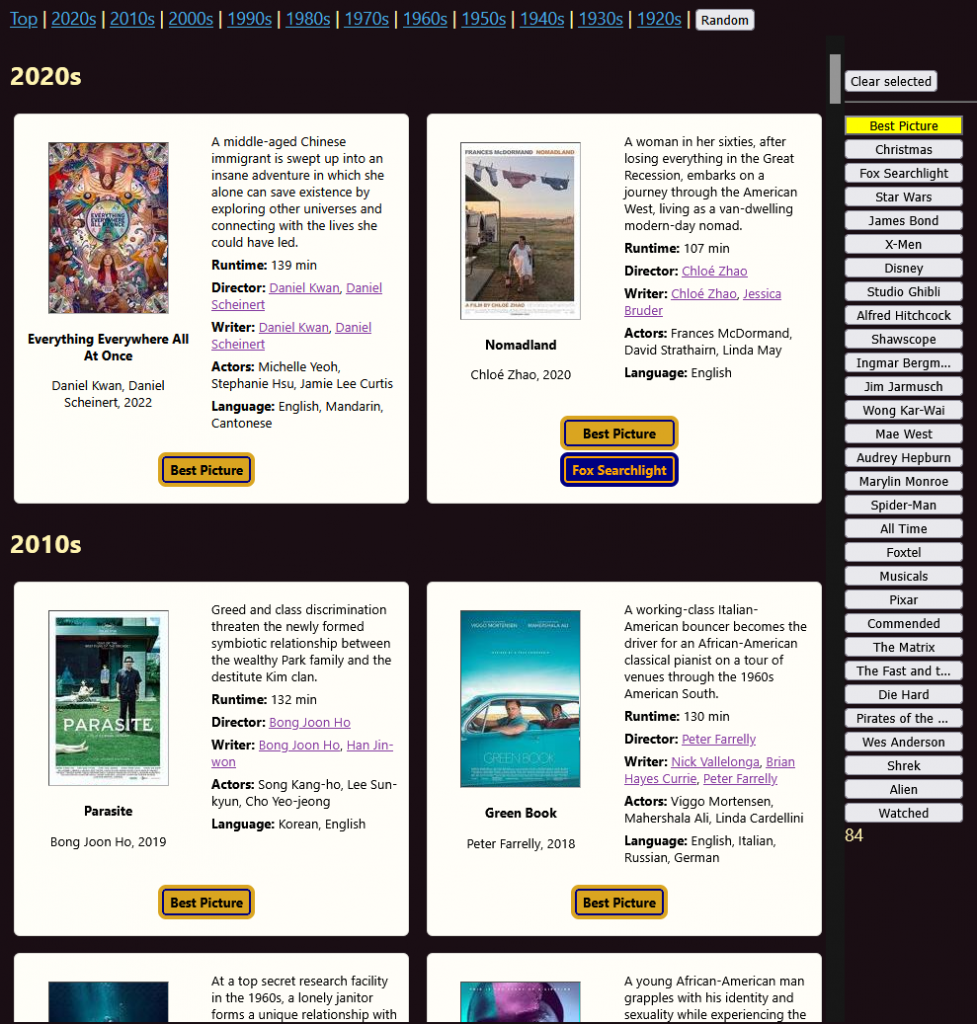

There it was – a fair way to go, but a working proof of concept. It’s come quite a way and integrated into the main app now – fast forward to today and I have 84 Best Pictures so far – which you can filter on in the main app:

A Dead End – Pop-ups

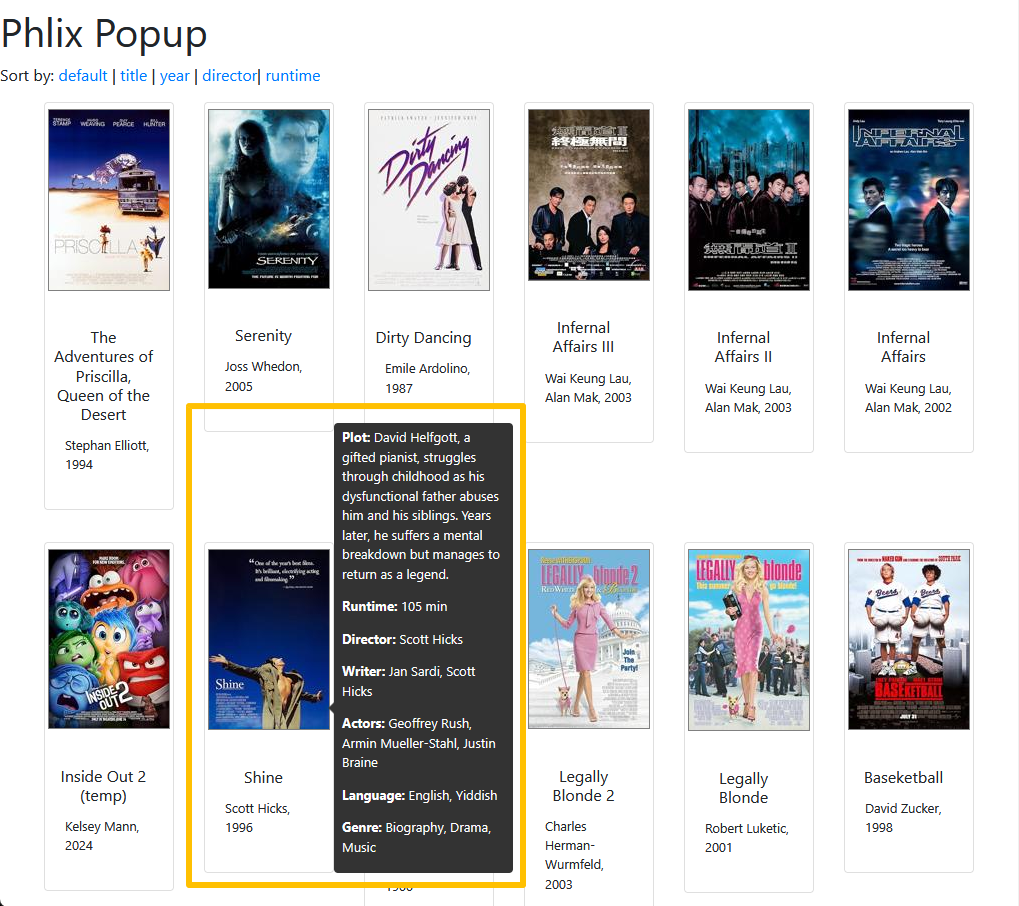

Around this time I thought about different ways of displaying the data, and whether pop-ups would be useful for managing information density?:

To get this up and running, once again I just cloned the endpoint and this time the template as well, and made some template adjustments.

I tried out my first (and only) 3rd party JS toolset, popup.js. It wasn’t terrible in theory – did what it said on the tin. It gave me some interesting ideas where it had already handled specific problems (e.g. where to position the pop-up when it’s near the edge of a window – you can see here how it goes up, rather than down, so that it’s all on-screen, rather than obscured off an edge.)

However, I just really didn’t like the feeling of outsourcing to a 3rd-party library – it was a quick one, but as soon as I wanted to start tinkering and tweaking I felt it would be a frustrating experience trying to unpick how everything worked. For example, this was a hover state – what if I wanted it click activated? What if instead of a pop-up I wanted this in an info panel on the side? It just doesn’t sit well with me, so while I have the luxury of building my own thing, I will. As little outsourcing as possible.

As it turned out I didn’t like relying on pop-ups to view details anyway. I wanted the maximalist view, as it was more suited to my browsing and exploration. Popups just introduced friction. Again, there’s an interesting piece to explore about information density, primary information, secondary information, interfaces, objectives etc. I didn’t just want to fit as many entries as I could on the screen (the approach Plex takes with its thumbnail view) – I wanted to explore. I could see how this would potentially be useful in other circumstances, but not now.

Pop-ups were out.

Image Management

In the first iteration, each movie entry in the database had a movie thumbnail file. The template simply included a reference column for thumbnail filename, and that was used in the source path in the HTML.

Two immediate issues here:

- OMDB provided larger image files than I wanted to display. This meant the page was much more resource intensive than it needed to be, both at the back-end (transferring larger files), and at the front end (holding larger files in memory and having to resize them in the browser.)

- As the collection grows, it becomes… a lot of requests. If each movie makes its own image request to the server, that’s currently 750 additional requests that get processed every time the page is loaded, and then the browser waiting and actioning 750 responses. That’s more load time, more compute, more energy. Madness.

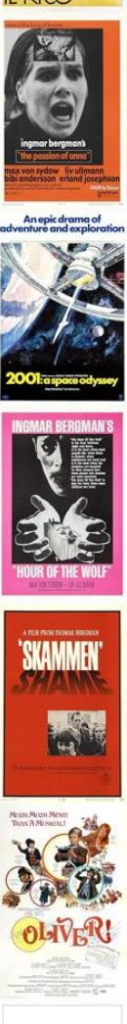

I’d seen CSS sprites used a few times before – basically, connecting up all images into a single file, and then using CSS to provide narrow coordinates of the bigger picture to display the section you needed. It looks a bit like a film strip:

Instead of loading an image file for every movie, the idea would mean that with one server call it would return MANY images in one go, and the CSS would then position it to show the right one. I thought decades would be a useful way of collating, balancing size and efficiency. Instead of 750 tiny server calls, each page load would now make just 10 big requests for images.

To achieve this, I needed several things.

- The posters I’d downloaded via API from OMDB were too big, so I needed to resize them (and compress them so they didn’t take up as much space). I did this by having the server call a Python package PILlow, an image manipulation library.

- I needed to stitch the appropriate ones together, in the right order. Again, PILlow to the rescue.

- Now I didn’t need the original image file location in order to display it – I needed the sprite image file, and the coordinates (which I calculated). I had to modify the movie table to store this info, and modify the template.

- Finally, I needed a way to integrate this into a workflow. At first, I had a lot of manual steps and triggers. Every time a new movie was added, I’d need to update the sprite and the coordinates semi-manually, as they were sorted by year and would fall out of synch. Eventually, I integrated this into the “add new movie” workflow, so that’s taken care of during the API search and save.

It mostly works, and that’s mostly where I’ve left it for now. There are a couple of pros and cons to each approach – the pros are above, but the cons? There are a few that surface. One is that right click -> view image doesn’t give you what you expect. Instead of the individual poster thumbnail, you’ll get a filmstrip of very poster of that decade.

Second, and probably more important – the size is hard-coded into a style element, which makes re-sizing to anything else not really possible.

Third – there’s more brittleness to the system. It’s more finicky. Less flexible. More constrained. Less intuitive. More chances for something to go wrong.

None of these are dealbreakers for me at the moment, though they may have consequences down the line.

There are still megabytes worth of image files (750+ legible thumbails!), but sprites make them feel much more manageable for the time being.

Layout 2.0 – I heart CSS display: grid

Around this time I paused development on my mostly-working movie catalogue prototype, and switched to building my platform’s layout mechanism. That’s the story for another post, but essentially, I got very familiar with the (relatively recent) addition of the CSS Grid layout, and I LOVE it. It solves SO many old problems with CSS layouts, and while it’s a tricky syntax to master (and I’m probably only 40% of the way there), it’s SO powerful and fun to use.

Across the site, layouts and colour schemes got templated and updated. On the movie catalogue, the Bootstrap CSS framework was out (which uses the similar but slightly-less powerful display: flex); display:grid with custom CSS was in.

That’s largely what you’re seeing now.

It was looking prettier, so at this point I started dabbling with interactivity. The first port of call was navigable sections. See these guys?:

They’re dynamic section navigation links, based on what comes out of the original database query and order. As the template is populated, it tracks the current section and section changes – whether that’s (currently) year or title; adds in section breaks; and then adds in navigation menus. I have movies from every decade since the 20s and beginning with every letter of the alphabet, so it displays all, but if I only queried a subset from my database it would skip over where there’s no entries.

This feature is not complete. There are a few quirks and gremlins. For example, I haven’t programmed up sections for sort by runtime or director yet, so it shows an “undefined” if you’re in those views:

An interesting consideration here is that we’re starting to get features interacting with other features, creating gaps and errors. We’re no longer building single proof-of-concept pieces – the interaction of functionality means complexity is increasing exponentially. I don’t just need to write rules for one sort order – I need to write them for each sort mechanism I create (currently five). An alternative would be to start considering ‘graceful fail’ options – i.e. a default way of handling something if pre-conditions weren’t met (in this case, the mechanism for creating sections for that particular sort mechanism.) The more I abstract, and the more complex interactions I introduce, the more I need to think about gap handling.

A couple of other interesting little quirks pop up, one of our first instances of an edge case having unexpected consequences:

Notice the lower case “s” after the “Z”? That’s because of the 750+ movies I have, one title is stylised with a lower-case letter: Soderbergh’s very important (to me as an indie film scholar) 1989 film sex, lies & videotape. The code I wrote inadvertently distinguishes case and arranges upper before lower. Because sections are generated programatically, we have unanticipated (though logical) behaviour. It’s reasonably trivial to fix, but I’ve left it in for now as it’s a useful reminder to reflect on – this will happen more as we increase complexity.

A few earlier examples – a handful of movie titles didn’t work with the OMDB lookup, whether it was because it couldn’t find them, or because it only returns the first option and it matched the wrong film, or it does exact matches only. I had to build a variety of workarounds. Another edge case – for some reason, some films don’t return poster images, or they’ve got non-standard dimensions. Some things I’ve addressed, some things I’ve created workarounds for, others I’ve left for the time being.

These are your 20% cases in your 80-20 rule.

***

I’ll pause there. Click on the section nav menu, jump around a bit and explore. Neat! Next up: randomness, selection, filtering, categories (and what’s the difference?!) See you in a year?

Flotsam & Jetsam

Flotsam & Jetsam

Watercolour Whisky

Watercolour Whisky Filmspotting

Filmspotting